Extra, extra

Click here to add text.

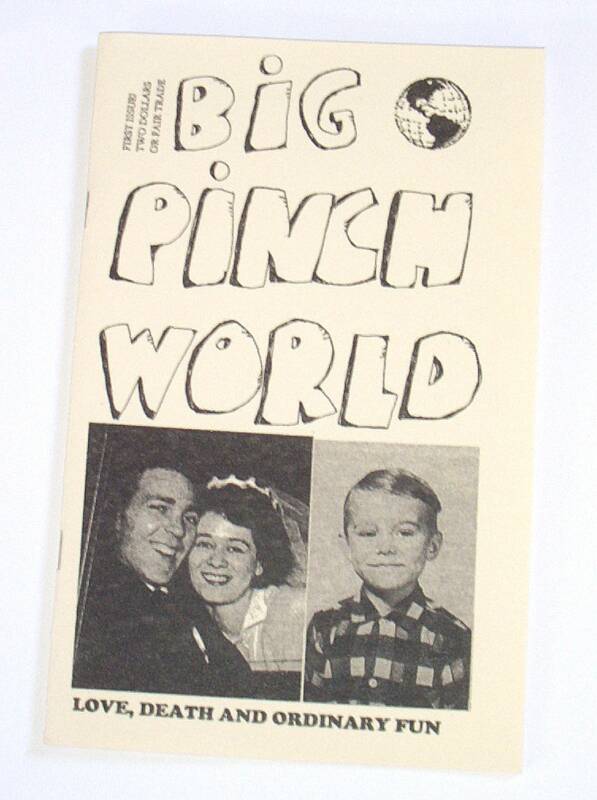

This one, which is not in the hard-copy BPW , deals with she who has much to do with the work's origins and with mine -- deliverer of the original wound, you might say (the pinch!), ultimate healer and guardian.

QUARRY

When I was eight years old, my grandmother told me a story about a husband and wife living with their new baby in the mountains beside a forest in Virginia. One black night they set out to visit friends. The man left the house first and the woman followed in a minute or so, baby in her arms. But she had left a lamp burning, or forgot her purse, something like that. She handed the baby over the fence to her husband, told him to start the car and hurried into the house.

A few minutes later she was in the car.

Her husband said, “Did you see that bear?” She said no and asked him where the baby was. He asked her the same question. The baby was gone.

“McKay,” my grandmother said, using my nickname, “in the dark she thought the bear was her husband. She handed her baby to the bear.”

I said, “What happened to the baby?”

She said, “The bear ate him, I suppose.”

I wanted to believe the boy was raised by a family of bears, like my grandmother raised me after my parents got divorced. She fed me and let me run wild – watching over me with less vigilance, I guess, than a bear mother but she had a household to maintain, other kids to look after.

Most of her tales fell somewhere between fact and fiction, and she presented even the craziest ones as literally true. Sometimes I would say, “That can’t be. It couldn’t have happened,” and she would say, “Oh, McKay, aren’t you the doubting Thomas! The doubting Tommy!” she said, calling me by my first name as only a few in the family did.

She loved the Bible as literature, along with Dickens, Poe, Hawthorne. When she told me stories from books, she would say the author’s name and immediately her voice became thin and her eyes filled with tears. Whether she was talking about Pip’s adventures in Great Expectations or the curse on the Pyncheon family – “God will give you blood to drink!” – in The House of the Seven Gables, she would pull that handkerchief from the pocket of her apron and wipe her eyes. I felt responsible but I wanted more stories. She gave them to me, and cried, and went back to work in the kitchen or sewing someone’s clothes.

For a while my mother had the idea that, on days when she could get away from her job early, she would pick me up to spend the night with her in the apartment across town. Next morning, we would rise with the sun and she would drop me off at my grandmother’s house.

This worked out all right for a while. But at some point I noticed that I became tired about the time the sun was low in the sky, 5:30 or so – well before dusk, long before that hour when infants get handed off to bears. My grandmother would send me to bed. Later I heard my mother downstairs.

“What do you mean he’s in bed?”

“Well, the poor little fellow was sleepy,” she would say. (She referred to all children as “little fellows.” When I showed her my first daughter, she looked into the bundle and said, “Oh, isn’t she a cute little fellow!”)

After my mother drove away I jumped out of bed and ran downstairs, and my grandmother served me a hot plate of pinto beans on a slice of spongy white bread. I ate and ran off to find my friends. I felt her smiling behind me.

Shortly after I came to live with my grandmother, her husband left her for a woman he met at the power plant. Carl filed for divorce; she fought it and won, which was possible in those days and seemed worthwhile, but he never came back.

One day she packed us all into the car and drove several miles to a house on Summit Street – one that we would come to know well as the visits repeated. She parked around the corner and let us out. “Stay on the sidewalk,” she said. “See what you can see.” She patted her hair, drummed her fingers on the steering wheel. We came back and reported what we saw. An open window, a lace curtain blowing in the wind. Always the same.

There was a market down the block with an ICE CREAM sign. I often had change in my pocket, but rules about our missions forbade any deviating from the course: Stay on the sidewalk. Make one pass around the block, then return to the car. See what you can see. One spring afternoon, I violated protocol and I marched across the street.

The move caused an angry stir and later in the car, as the sticky rainbow sherbet melted and flowed onto my fingers, as I crunched into the cone, Mad scolded me. But she didn’t throw herself into it, disappointing the other kids as she delivered what amounted to not much more than a recital of my wrongness, a speech without any of the animation or sincerity of her stories.

One Thanksgiving way back, before the family broke apart and became spread around the country, I said to one of the other kids – we were not kids by this time, of course – “What will become of us when she dies?” We didn’t want to think about it and went back to our food. Then she died, and we came back to Illinois for the funeral, and discovered there wasn’t much to think about. Just the brain-stopping fact of what we believed would never happen, even though we knew it would, and how everything on Thanksgivings from that point forward would taste even less good than it had in quite a while already.

About two years ago, I saw her after a long absence. I had been roaming around the country, divorced, lost; she was in the nursing home but still lucid at intervals. I wanted more stories.

“Do you remember when we sat on the porch in the summer and you sent me up to Steak ’N’ Shake to get us a nice cool drink?” She always called it a nice cool drink. “Do you remember when we saw the stars dancing in the sky over Kishwaukee Street from the bedroom window?” They made quick patterns like nothing I had seen before or have seen since. It was before we had heard the term ‘UFO’. “Remember when the cat peed off the second-floor balcony, right onto Mitch Rumore?”

Soon she was laughing.

She said, “Oh McKay, when you say these things, it’s all spread in front of me like a book.” She stared into the air between us. “That poem, do you remember it?” Her eyes filled. “Abou Ben Adhem.”

The poem is by James Henry Leigh Hunt, who lived in the late 1700s to the mid-1800s. It begins, “Abou Ben Adhem (may his tribe increase!) / Awoke one night from a deep dream of peace,” and goes on to tell how Abou found “an angel writing in a book of gold” when he woke.

Abou asks what the angel is writing. The angel replies, “The names of those that love the Lord.” Abou wants to know if he’s included. The angel says, “Nay, not so.” Hearing this, Abou speaks lower but “cheerily still,” and asks to be written down as “one that loves his fellow men.” The angel writes, then disappears.

One night later the angel returns “with a great wakening light, / and showed the names whom love of God had blessed, / And lo! Ben Adhem’s name led all the rest.”

Another of her sappier and better-known favorites has an angel. It’s by Eugene Field, who also lived in mid-1800s. He’s often referred to as “the poet of childhood,” and she liked everything he wrote. The poem is “Little Boy Blue.” The first part goes like this:

The little toy dog is covered with dust,

But sturdy and stanch he stands;

And the little toy soldier is red with rust,

And the musket molds in his hands.

Time was when the little toy dog was new,

And the soldier was passing fair;

And that was the time when our Little Boy Blue

Kissed them and put them there.

"Now, don't you go till I come," he said,

"And don't you make any noise!"

So, toddling off to his trundle-bed,

He dreamt of the pretty toys;

And, as he was dreaming, an angel song

Awakened our Little Boy Blue – ”

At this point the poem seems interrupted by some unknown event. Then it resumes:

“Oh! The years are many, the years are long,

But the little toy friends are true!

Aye, faithful to Little Boy Blue they stand,

Each in the same old place –

Awaiting the touch of a little hand,

The smile of a little face;

And they wonder, as waiting the long years through

In the dust of that little chair,

What has become of our Little Boy Blue,

Since he kissed them and put them there.”

When my grandmother first read me this poem I asked, “When that angel song awakened the little boy, did he die?” Bad enough that kids got carried off by bears. Now they were dying in their trundle beds before they could get back to their toys.

She said, “Yes, McKay, I suppose he did.” She told it like it was, or like the story said it was.

That morning in 1967 after we got the news about Carl, she thrashed and wailed on the sofa. One of my uncles tried to comfort her. She wanted to die. It was like on TV when survivors in faraway countries mourned their dead. I watched from the corner.

Later she told me the midnight banging on the door had jolted her from a dream of him and all of us in Atwood Park, where in the old days we’d gone for picnics. He appeared to her in the canyon-like rock quarry at the edge of the park. Forbidden to kids in real, waking life, the quarry had steep craggy walls that – in her dream – we clung to, high up, paralyzed with fear.

Carl said he wanted to come home.

“And just where do you think home is?” my grandmother said. She had him now. She had him.

“Why, home is wherever you are,” he said.

I wish I could be postmodern and ironic. I want a way to push off the strangeness and sorrow, a technology to make me seem wise in the face of what I don’t know and am afraid to feel, or both. I want that but I can’t do it. I might if I could, like I might accept a million dollars in stolen money if no blame could be traced to me. But it would be, so I can’t.

Nor is the maudlin route available, along which I speculate whether the angel who visited Little Boy Blue might be the same who claimed my grandmother in her sleep. A host of bad, obvious metaphors await plucking, as in: For months after her funeral I felt like Boy Blue, or at least like a little boy again and blue, missing her. Or how about: I was a toy soldier kissed, set down and left behind to gather dust and wonder for the rest of the years.

Nothing works. What I have in my hands are stories – the ones she told me and the ones I make up, offering them to the absence where she was. The kind of stories you tell in a quivery voice with bright shining eyes.

| ||||||

You want to visit my blog, yes?