Kick back, settle in

BRINGING DAD HOME

A filmmaker named Eric told me a story about scattering the ashes of his older brother into their favorite boyhood creek in upstate New York. Late one winter afternoon, Eric popped the lid, shook out the crumbs and pieces, and watched the current take them away. He said a prayer. As he walked back to his car, the season’s first snow began to fall, delicately, like a benediction.

Eric said it would have made a fine shot in a movie – just as when, weeks later, he went back and wandered along the ice-crusted edge of the creek. Like a graveside visitor he spoke to his brother. Puffs of his breath floated away on the air.

“I could almost feel his hand on my shoulder,” even through the heavy coat, Eric said. The sun was low, a few stray flurries blowing around. Sad as he was, Eric couldn’t help thinking again that the scene was perfect, from a cinematic point of view.

“I came to a bend where a tree had fallen, a backwash,” Eric said. “And there he was. My brother. He was congealed into a gray, frozen clump, mashed and hardened against the bark of that tree.”

Someone at the dinner table tried to laugh at what might have been Eric's punch line. A woman stared at her hands. “It looked like a huge barnacle, or some kind of obscene, petrified sponge.” No one spoke. “I wanted,” Eric said, “to gather him up.”

*****

My father, from his hospital bed year before last, said to me, “You know what I miss? Walking on a winter night, late, when it’s so cold the snow crunches under my shoes and it’s quiet except for some faraway traffic noise, and I’m walking under the streetlights. I can feel the air coming up my pant legs and I’m just walking.”

Dad shook his head. “I think crazy things now,” he said. “I have dreams. Like, me and Al Nightingale went hunting and I couldn’t make the goddamned wheelchair go through the mud. So I got out, folded it up and walked with it! I had my gun in one hand and the wheelchair under my other arm.”

The nurse brought a paper cup of water and three pills.

Al Nightingale was a buddy of Dad’s in Rockford, Illinois, when my parents were still married and we lived on Thelma Street, before the divorce and Dad’s disappearance and wandering.

Dad had been cleaning his gun in the kitchen. Mom was bitching about housework and Dad’s general lack of initiative. This was during a period of heavy drinking in my father’s life, and he was polishing the barrel of his gun while Mom complained, and he said to her in a slurred voice, “I could put you out of your misery.” Minutes later Mom had me and a bundle of clothes piled in the car. We never went back.

Dad had lost touch with Al Nightingale more than 30 years before. I had lost touch with Dad for almost as long, but when I grew up I found him again, out on the flats of Colorado where he’d ended up living with his mother. She had died and Dad was alone in the big house. It was a period of heavy drinking in his life but we began to put together a long-distance relationship. Then, his accident.

He must have fallen when he stood up from his chair in the TV room, and lay on the floor for two days, twisted “like a garden hose,” the specialist in Greeley told me. Dad was paralyzed from about the middle of his spine down.

I came from Georgia to get him. So he could travel, Dad was rigged with a catheter that ran from his bladder to a plastic bag tied on his ankle. It was taped to his leg under his clothes. You would never know he had it, but the bag had to be emptied every few hours or the poison would back up in his system.

I was half asleep on the airplane when Dad began rooting in his knapsack.

“Excuse me,” I heard him say. I woke up. I thought he was talking to me. In his shaky hand he held out to the flight attendant a small, square bucket full nearly to the brim with bright yellow liquid.

“Would you empty this for me?” he asked.

“What is it?” she wanted to know.

In a flat, calm voice he told her. She screamed.

I got Dad into an assisted-living home in Georgia and stayed for a couple of years. Then my own divorce and wandering took me all over the West, to places Dad had been and places he hadn’t. I didn’t plan to retrace his footsteps. I didn’t even know where his footsteps went. I just roamed, like he did, like men often do when they are heartbroken by failure and don’t want to stay in one place long enough for it to show. I landed in northern Illinois, less than a hundred miles from the town where it all started for us as a family.

In March, Dad’s doctor called from the VA hospital in Augusta. “The time has not come, but your father has given us instructions,” he said. “However, we need some documents from you before we can implement the advance directive. He doesn’t want anyone jumping up and down on his chest. Artificial resuscitation, you understand.”

They had amputated his useless legs, bloated and marked with infected bedsores. He had been diagnosed with leukemia, his blood pressure had gone haywire and his kidneys were failing.

The doctor called again in April.

“He was in and out of consciousness,” the doctor said. “He had refused food and water. Early this morning he woke up, looked around and said very clearly, ‘I’ve had enough. Shut everything off. I’m ready to go.’ We proceeded in accordance with his wishes. I’m sorry. I suppose you’ll be flying down.”

Returning from Georgia with Dad’s ashes, I handed the metal box to the woman at the airport security gate in Atlanta, with a certificate provided by the crematorium. She read the paper and looked at me, horrified, as if I’d handed her a bucket of pee. She shoved the box into the arms of another security person. I walked through the gate. The alarm went off.

“Over here,” a man said, pointing to an X taped on the floor. I went to him but kept my eyes on the ashes. They had been relayed to a third security person, who was looking around for a handoff.

The man ran a wand up and down my spread arms and legs.

“We need you to remove your shoes,” he said. I did. He rubbed one of my shoes with a piece of fabric held in some tweezers. He put the piece of fabric in a big machine. The alarm went off. Men with guns strapped to their shoulders came over.

“Can I have my Dad back?” I said. He was sitting on a table with the certificate on top of him. The men with the guns moved closer to me.

Someone in a suit came over with a spray can. He sighed and said, “Nobody panic.” He opened the machine, sprayed and did some slow, methodic wiping with a paper towel.

I said, “You can keep my shoes. I’m going to miss the plane. Please let me have my Dad back.”

The man in the suit, ignoring me, slammed the metal door shut and sighed again. He pressed a button on the machine. My shoes passed.

With Dad in my lap on the airplane, I thought of the other jet ride we had taken together and how things had gone for him before and after. “I’m sorry about the Popsicles,” I said – quietly, it seemed to me, but a woman two seats away tilted her head and stared at me. My earliest memory of Dad is in the house on Thelma Street, winter. Our freezer was broken and my mother had put my Popsicles in a snow bank outside. I wanted one. Mom asked Dad to get it. He started yelling and turned our table over with a crash and broke our plates.

I’m sorry about what happened in California, I said, this time in my head.

After Mom and I left him, Dad had quit his postal-clerk job and gone to Australia with a dream of mining for opal in the desert, which he did. He met a woman on the ship who wanted to live in the United States. She got pregnant and they married. Dad, settled again in an ordinary home outside Los Angeles with another child, was depressed. This was during a period of heavy drinking in my father’s life, which made the depression worse. His wife signed papers for shock treatments. When they let him out of the hospital, he went back to Colorado to visit his mother, and when he returned to California, all of his belongings were on the front lawn. She had warned him in a letter. He was getting divorced again.

“I’m sorry,” I said once more, aloud.

Then, 35,000 feet above the ground, my father and I drifted into one of our many conversational lapses. A similar period of vacuum-like silence had taken place a few months after his accident.

Sunday afternoon, Georgia. He had just finished begging me to get him a handgun. We argued. Assisted suicide, I said. The Bible Belt prosecutors would put me away faster than you could say “Jack Kevorkian.” Things will get better, I said, having no idea how they might.

Dad said, “I can get a gun without your help. I know how to get one.”

I said, “You’ll have to do it that way then.”

He held his head in his hands and wept. He took a long time to stop. The courtyard was full of birds and I watched them.

I told Dad I knew a woman who was considering an abortion. Something dramatic was called for at that moment, something that did not involve us, and I came through. Dad sniffed. He wiped his nose with the back of his hand and rubbed his face.

“You can’t ever know,” he said.

I suppose he meant you can’t ever know how life will turn out, or what plans to make.

He said, “It’s not the worst thing.”

Then he said, “Your mother had an abortion.” The birds were mostly sparrows, with a bright male cardinal hopping through the flock.

“You were two years old,” Dad said. “She took care of it.”

I pictured the baby who didn’t get born as a brother. I couldn’t ask Mom, who might have been told by the surgeon -- the one who scooped out the embryo like a glob of snot, I imagined, and whacked it into a trash can -- because Mom was no longer with us. They found what was left of her in the old farmhouse outside Rockford, where she had been living with her Salem cigarettes and potato vodka and the curtains drawn.

“Your father called me yesterday,” she told me one afternoon when I was up from Georgia to see her. “He wanted to tell me how sorry he was about how everything turned out between us and how it was all his fault, and he said he didn’t know how to treat a woman in those days but he does now and it’s too late. I hung up on him.”

I asked Dad about the conversation. He said, “Yeah, I called her. I said all that. I called her back and said, ‘Hey, don’t you hang up on me!’” We both laughed.

*****

I picture my brother as an adult man now. He would walk with me when the weather is better, Dad’s birthday in August maybe. Together we would scatter the ashes of Dad into the lakes and streams of northern Illinois where he fished in the days when he had legs. I fished with him once or twice, or I sat on the grass and watched; my recall of those early times is not complete, and Dad’s was taken by the electroshock.

My brother would carry the box. He will carry the box. He will open the lid, plunge his hand into the ashes and fling them, making them free. I, the older one, will try to say a prayer but I’ll stammer and pause, godless, and my brother will speak the rest of it, clear and strong across the sun-rippled water, like in a perfect movie.

When he’s finished he will sink to the grass. I will kneel beside him and put my hand on his shoulder. I will gather him up.

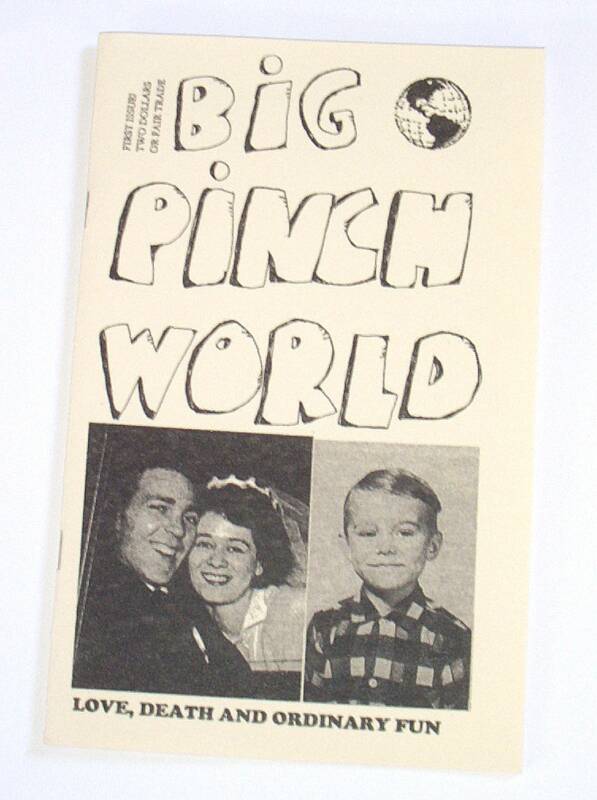

The essay below is contained in the hard-copy version of BPW #1, which you might already have put yourself through. Yes? Thank you. It was originally published in the Chicago Reader, has undergone changes over time, and is the lead essay in my book (in progress). There'll be plenty of fresh material in the book, and I think we can take "fresh" in various senses of the word. Bold and saucy! Impudent! And not, with any luck, stale.